From the Executive Director

Killer in the bottle: methanol poisoning is the hidden epidemic

Time flies, and as the year is coming to an end, it’s common for people to get together with family and friends during the festive days of Christmas and New Year to have fun and grab a few drinks. For most people, drinking too much at a party would only result in getting hungover, but if you drink poor-quality alcohol laced with methanol, it may be the last drink you’ll ever have.

In the Asia-Pacific region and the Middle East, home-brew alcohol is common, especially in the countryside and poorer areas. These homebrew alcoholic beverages are often consumed at marriage ceremonies, funerals or banquets, and as a result, methanol poisoning happens frequently. It is a huge public health issue; and the COVID-19 pandemic makes it even worse, as many countries are under lockdown, making it difficult for people to go out and get supplies. At the same time, rumours about how rubbing alcohol could prevent COVID-19 has led to the illegal sale of rubbing alcohol that contains methanol, intensifying the severity and complexity of the problem. Even developed countries are now facing this issue. However, many people still overlook this problem for a variety of reasons.

The most common misunderstandings are about causes and symptoms. Most victims of methanol are poisoned by drinking alcohol laced with even cheaper methanol, which is a similar compound used as a solvent or for anti-freeze. The effects of metabolising methanol are similar to that of drunkenness, for example, vomiting and feeling dizzy. Many people would simply treat it as drunkenness, and let the patient drink some strong tea or sleep. However, if that “drunk person” happens to be poisoned by methanol, and does not receive medical care in time, they could face serious consequences, such as the loss of their vision or even death.

To confront this often overlooked problem, MSF has been cooperating with Oslo University Hospital since 2012 to start a series of projects to prevent methanol poisoning. These are now underway in a number of different places, such as Indonesia, Libya, Kenya and Russia. Part of the campaign is to raise awareness about the issue so there is a wider understanding of the risks.

Saving lives is not something that only healthcare workers can do. Although we may live in a place where methanol poisoning is much less likely, this issue of Borderline may one day help you prevent someone from being poisoned or even dying from what has been an almost hidden hazard.

Jenny Tung

Executive Director, MSF Hong Kong

Crisis in focus - A drink to die for?

Delicate wine can be enchanting, but if you drink too much, the intoxication and the hangover that follows aren’t that enjoyable, and excessive consumption of alcohol in a long run is harmful to your body. If the wine is adulterated with methanol, it can be deadly. Methanol poisoning is a public health crisis that health workers and everyone else must watch out for to avoid preventable deaths. In recent years alone this neglected disease has caused so many severe health consequences and deaths.

In March 2021, there was a mass methanol poisoning outbreak affecting nearly 450 people in Santo Domingo, the Dominican Republic, and over 150 people died. In May, India also had a large-scale incident in which nearly 120 people were poisoned and 87 people killed. Methanol poisoning outbreaks may sometimes make the news but despite that, every day in different parts of the world, people take risks on a bottle of cheap alcohol. The impact may not be visible but it’s doing harm more often and more seriously than you think. It’s worth taking a close look.

5 facts about methanol poisoning

1. Methanol vs Ethanol

Methanol is also known as wood alcohol or wood spirit. It is a widely available chemical used industrially as a solvent and as an alternative fuel source. It can also be found in some of the consumer products in our daily lives, such as inks, dyes and cleaning products. Exposure to methanol can occur through inhalation, absorption through the skin, and most commonly through ingestion. When swallowed, most of it becomes formaldehyde in the body, which then rapidly metabolises to become highly toxic formic acid and its anion formate. However, the reaction for intake through breathing or the skin is much slower.

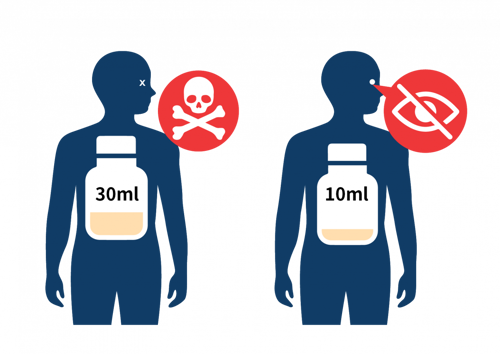

Consuming too much methanol can cause cell failure and nervous system damage. Its toxic dose depends on the concentration and the timeliness of treatment provided to an individual. As little as 30ml (about a mouthful) is reported to be the minimum fatal dose for an adult, and 10ml (2 teaspoons) can cause blindness. If left untreated, symptoms typically evolve into coma, brain damage, and death.

Ethanol is the other closely related alcohol compound that is mainly used for household disinfection and general alcoholic beverages. It is safer. However, both are transparent and colourless, and there is almost no difference in taste and odour. Therefore, it is difficult for us to tell them apart. In Hong Kong, methanol is generally marked with a "toxic" hazard warning label, and a purple color is added to distinguish it from other alcohols.

Methanol is also found naturally in some fruits, vegetables, alcoholic and non-alcoholic fermented beverages. The more mature fruits produce more methanol. However, we do not need to worry because methanol that exists naturally in this way is harmless to the human body.

2. The history of 'illicit wine'

The development of the purification process of methanol in the late 19th century has made the use of methanol easy as a cheaper substitute to ethanol in adulterating alcoholic drinks. It was reported that as late as 1910, many wines, brandies and whiskeys sold in New York contained methanol as a proportion ranging from 24% to 43%. Although there were sporadic cases of poisoning after ingestion, they were attributed to contaminants and impurities at that time rather than methanol. It was only in 1923 when a group of dockworkers in Hamburg, Germany was poisoned by chemically pure methanol that methanol poisoning became known.

Even today though, with the challenges in identifying cases of methanol poisoning, it is presumed that the number of reported cases is just the ‘tip of the iceberg’, underestimating the true scale of this neglected crisis. To respond to this situation and for further research, MSF set up a news database of suspected methanol poisoning incidents happening worldwide, constantly updating it.

3. Methanol poisoning does not mean getting drunk

Although the symptoms of methanol poisoning and drunkenness can be very similar, they are definitely not the same thing. Vomiting, abdominal pain, headache, dizziness, and unsteady gait are common adverse effects when people get drunk. However, to the person with methanol poisoning, they are only a prelude. Methanol poisoning occurs when methanol is metabolised into highly toxic formic acid. It takes about 12 to 24 hours or even more for symptoms of poisoning to appear. The chemical reaction takes time, with people usually feeling sick after 6 to 12 hours, or even as a delayed effect around 18 to 24 hours.

The most obvious symptom is visual impairment, which is the clearest clinical distinction between patients who are ‘just drunk’ and those with methanol poisoning. The other symptoms include hyperventilation, dyspnea or shortness of breath, gastrointestinal pain, vomiting, and chest pain. Without specific treatment, patients become unconscious and die within a couple of days. The symptoms typically last a few days for majority of the patients, with some exceptional cases that have continued for weeks or even months. The mortality rate is usually 20% to 40% if no treatment is applied.

4. Can methanol poisoning be cured by drinking ethanol?

At present, there are two treatment regimens for methanol poisoning. One is to take ethanol as an antidote, and the other is to take fomepizole. The former can be injected intravenously or swallowed. Some people describe this as “treating alcohol intoxication with alcohol”. In short, methanol poisoning is mainly due to the strong toxicity of formic acid. To create formic acid, methanol must be decomposed by alcohol dehydrogenase, ADH for short, in the liver. However, if methanol and ethanol are present in the body at the same time, ADH will decompose ethanol first. When the concentration level of ethanol in the blood is high enough, the ADH is saturated and there is none left for the methanol. So methanol can no longer be converted into toxins and is excreted from the body. Even if this process is not as smooth as expected, healthcare workers and can buy time to implement different medical solutions for the patient, such as haemodialysis. But this method needs trained healthcare workers can make things worse if implemented inappropriately.

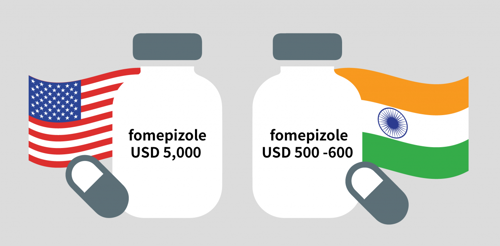

Using fomepizole, as an antidote to methanol poisoning is far more effective and safer. The principle is same as the above method, which is to avoid methanol metabolised into highly toxic formic acid. Fomepizole does not cause sedation or behavioral changes in patients and it may reduce the need for intubation or dialysis. However, fomepizole is very expensive and unavailable in many parts of the world. US pharmaceutical companies sell it for up to US$5,000 per vial, while Indian manufacturers list their price as US$500- $600.

In 2013, fomepizole was included in the World Health Organization’s recommended list of Essential Medicines. However, due to a lack of data on methanol poisoning and the high cost of fomepizole, this antidote is not registered in most countries or approved for emergency reserves. MSF is therefore advocating for increased availability and accessibility to fomepizole.

5. Still a massive, deadly problem worldwide

Methanol poisoning is quite common worldwide. The special measures and policies under the COVID-19 pandemic make the problem even worse. For example, homebrew became more popular while lockdown policies were implemented in many countries. Some people even consume alcoholic sanitisers as substitutes for alcoholic drinks.

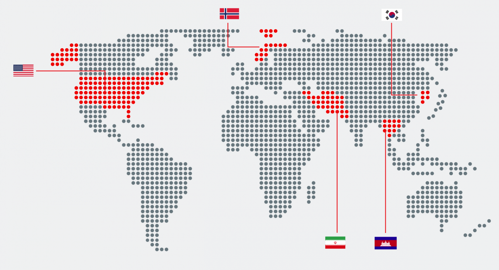

At the same time people are also exposed to misinformation/disinformation, such as using methanol as a disinfectant to replace ethanol or believing the rumours that methanol can cure COVID-19. That kind of information spread quickly throughout communities that were afraid of getting infected. Methanol poisoning is not only found in developing countries but also in developed countries such as the United States, Korea, and Norway.

Iran: The largest outbreak in recent years

In 2020, over 700 Iranians reportedly died and more than 5,000 fell ill, with 90 losing their eyesight or suffering eye damage after consuming methanol, amid false rumours that it can cure COVID-19.

Cambodia : Cambodian villagers killed by toxic wine at funeral

According to a BBC news story in July 2021, more than 30 people had died in three separate incidents across Cambodia between May and June, from home-brewed rice wine containing methanol. In Thnong village, 8 people who attended the funeral died due to drinking low-quality wine, and another 50 people were hospitalised.

Methanol poisoning is nothing new in rural Cambodia - homemade alcoholic brews are popular at wedding parties, village festivals and funerals as a cheap alternative to commercially produced beer and spirits. It is quite common that home distillers operate ramshackle stills inside their houses or shops selling this home-produced rice wine to their neighbours. There are no legal controls, inspections, or quality controls. Since the recent spate of deaths, Cambodian authorities have been attempting to show they are taking the problem seriously. They have called for people to avoid drinking contaminated alcohol.

Norway: Man dies of possible methanol poisoning in Oslo

In September 2020, a man’s death was linked to other people who were admitted to hospital with methanol poisoning. The police worried that more dangerous methanol-containing alcohol may be in circulation, and they needed to track where the alcohol came from. Though this case seems minor in scale comparing with the others, it showed that methanol poisoning is also found in developed countries.

USA: Several people have died due to ingesting hand sanitisers containing methanol

The Arizona Poison and Drug Information Center announced that from May to early July in 2020, four people died and 26 people were hospitalised after ingesting hand sanitisers with methanol. These sanitisers poisoned around 50 people overall and the number was still increasing. Some admitted consuming hand sanitisers as a substitute for alcoholic beverages and that resulted in symptoms such as visual disturbances or loss and severely altered mental status. It triggered an alarm because hand sanitisers are normally primarily ethanol or isopropyl, but those incidents showed that some of the products might contain methanol, which, as we’ve seen, is highly toxic and can be lethal.

Korea: Mother and child poisoned after using a methanol-based substance to disinfect her home

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, parts of Korea were suffering from a shortage of disinfection products. Some used methanol as a substitute for ethanol and that nearly led to a tragedy. In March of 2020, a woman in her 40s and her two children in Gyeonggi Province, Korea, were admitted to a hospital showing symptoms of intoxication, after the woman used a methanol-based disinfectant to clean her home.

MSF in Action - How MSF responds to methanol poisoning?

In response to the growing severity of the problem of methanol poisoning worldwide in recent years, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has begun work that aims to improve our ability to respond to the issue, as well as enhance public education. Through the video interview, Dr Nason Tan, the Regional Operations Support Unit Director of MSF Hong Kong, who is leading the Methanol Poisoning Initiative (MPi), will share how his team tackles the problem.

About MSF Methanol Poisoning initiative(MPi)

In 2012, the Methanol Poisoning initiative (MPi) was established as a joint venture between Oslo University Hospital (OUH) and MSF. We had operating MP programmes in Indonesia, Libya, Kenya, Russia etc. The MPi team found that most cases are related to the drinking of “fake wine”, ingestions of methanol by mistake, and occupations in industries that are prone to methanol exposure. So far, the team has supported three outbreak interventions in Libya and Kenya. We also implement trainings in Kenya, Russia and Indonesia; and supported the development of local treatment protocols in countries like Cambodia.

As a regional office, MSF Hong Kong has been part of MPi since 2018, aiming to improve the ability of MSF and our partners to diagnose, treat and respond to methanol poisoning, at the same time raise public awareness of this issue through health education.

The major obstacles & challenges

- The symptoms of MP resemble many other medical conditions - apart from a hangover and alcohol poisoning - such as sepsis, heart attack and stroke. This can be misleading for healthcare workers and makes it difficult to make an accurate diagnosis, potentially delaying treatment.

- In some places where resources are lacking, the healthcare workers do not have the tools for early diagnosis and treatment, even they know what MP is and how to treat this issue. For example, fomepizole, the most effective and fastest antidote for methanol poisoning, is very expensive and not even a registered medicine in most countries.

- Due to religious and cultural norms, drinking is not encouraged in some countries, and there may even be prohibition on the manufacture, selling or drinking of alcoholic beverages. As a result, people turn to black markets or home brew. This can be very dangerous if they get methanol poisoned because they often don’t dare to seek immediate medical care, fearing stigma or prosecution. Even if they go to the healthcare facilities, they might not tell the truth to the healthcare workers and that increases the risk of misdiagnosis. That gets even worse when the patients hide the fact that they were drinking with a group and it can lead to a high human toll.

COVID-19 impact

The outbreak of COVID-19 has been creating many new factors around MP. Disinfectants like hand sanitizer are now a much more commonly available commodity that is part of everyday life and if those products contain methanol, there is a risk of MP. Moreover, under anti-pandemic measures like quarantine, lockdown and the prohibition on group gatherings, people might not able to get a drink legally and turn to black market alcohol beverages or home brew. They can contain methanol impurities, that would pose a threat to consumers' health.

The pandemic has brought this public health issue to the surface and it is becoming better known. We need to seize the opportunity to enhance public education and work harder on monitoring. With people’s limited understanding of methanol poisoning, the reported cases in many places may involve missing information or misinformation, making it hard for us to have the full picture of the situation. We have tried to consolidate a database of suspected methanol poisoning cases from our news monitoring around the world. That gives us a better understanding of the pattern of this issue across countries.

According to the data we collected, between January and July 2020, at least 6,923 people were suspected of being affected by methanol poisoning, and 1,587 people are believed to have died from it. The figures in the same period this year have dropped, but are still higher than those before the pandemic. In the first half of 2020, when the pandemic was spreading fast, people were panic buying alcohol-based sanitisers and some of them may have contained methanol instead of ethanol. Some were affected by rumours suggesting that drinking methanol directly can cure or prevent COVID-19. We believe these might have caused the surge in the number of cases last year.

After a year of living under the pandemic, we see lowered risks of methanol poisoning from the use of alcohol-based sanitisers due to the improved public awareness of the potential harmful ingredients in these products, as well as a more stable supply in the market. However, we should stay vigilant. Methanol poisoning will still be a problem even if the pandemic slows down.

Watch the webinar recording on YouTube

[Neglected Disease] Methanol Poisoning: The Illegal Brew That Kills

Earlier in August this year, MSF Hong Kong organised a webinar that zoomed in on the challenges of diagnosing and treating cases of methanol poisoning.