On 11 March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic. Since then, scientists around the world have been developing vaccines faster than ever before to stop the disease from infecting yet more millions of people. As of 12 May 2021, with over 100 million cumulative cases and 3 million deaths, we have six versions of vaccines approved by WHO for emergency use. Despite the huge progress, the quantity of COVID-19 vaccines, medical tools, and therapeutics currently available are still far from sufficient to deal with the pandemic, especially when manufacturers are struggling to cater for the huge global needs. This harsh reality of scarcity will not change very rapidly, and the question at this very moment is how to make the very best use of the limited resources to protect those who are the most vulnerable.

Priority to the high-risk groups

They are the people at the highest risk of getting the disease or developing severe symptoms when infected. The WHO therefore recommends vaccinating these groups of people before others, with approved vaccines that are largely safe and effective, in order to reduce mortality and keep health care services running. The idea of extending the vaccination campaign to lower-risk groups in some countries before giving it to the high-risk groups everywhere undermines the recommendation. And now it's not only an idea; it is a development we are all seeing.

A reality crueler than the vaccine scarcity

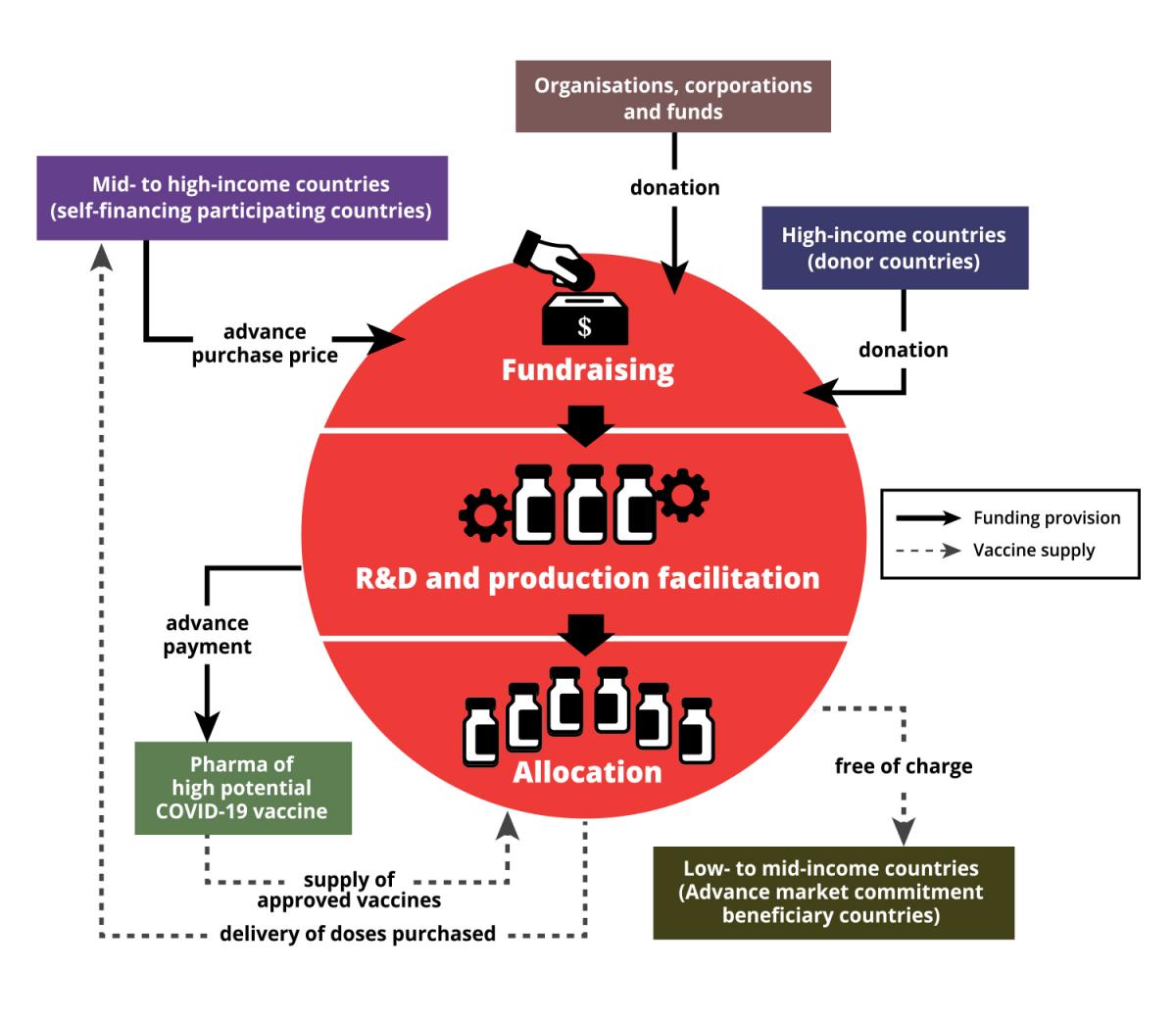

With the intention of helping equitable global access to COVID-19 vaccines, WHO, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) jointly initiated the COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX) Facility last year. COVAX aims to help countries protect their people who are at the highest risks regardless of how rich or poor the country is. The concept of COVAX is a bit of a mixture of the ideas behind crowdfunding platforms, group buying and suspended meals, but of course, it is much more complicated than that. It's more than just a funding instrument, as it also aspires to regulate the prices of approved and licensed vaccines. Below is our attempt to explain how COVAX works:

COVAX is the lifeline for many developing countries in this pandemic, because it's a formidable task for them to compete with richer countries for enough vaccines through bilateral agreements. The success of COVAX hinges solely on global solidarity, especially a show of strong commitment from high-income countries. But this solidarity is yet to be realised.

Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A) is a global collaboration to speed up the development, production and equitable access to new COVID-19 diagnostics, therapeutics and vaccines, and COVAX is its vaccine pillar.

"COVAX was built on the understanding that bilateral agreements would happen. What the problem has been is the extent of these bilateral deals," said Amanda Harvey-Dehaye, leader of MSF's ACT-A task force.

"Countries who have met all their needs uniquely through bilateral deals, and therefore don't need COVAX doses too, are supposed to inject money into COVAX anyway. This would leave COVAX able to negotiate with pharmaceutical companies for vaccines for the lower income countries this mechanism subsidises. But this didn't happen enough, and through all their bilateral deals, a few wealthier nations have hoarded up a vast part of the available supply – which is anyway less than hoped for, given the production problems and manufacturers over-committing," Amanda added.

Major obstacles faced by COVAX

As of March this year after the G7 leaders committed USD 4.3 billion to ACT-A, it still faced a funding gap of USD 22.1 billion to reach the target for 2021, and COVAX alone was USD 3.2 billion short. The disparity of vaccine supply also undermines COVAX's efforts for equity amongst nations through a pooling of resources. According to WHO, more than 800 million vaccine doses have been administered globally as of mid April this year, and over 83% of them have gone to high-income or upper middle-income countries, while low-income countries have received just 0.2%. Some wealthy countries and regions, including Hong Kong, have snapped up more than they need to create herd immunity in their societies. Quite a number of them even purchased more than double the number of vaccine doses that their entire population needed.

Countries like the United Kingdom and the United States of America started vaccinating their population in mid-December last year, while COVAX only managed to commence the first batch of vaccine delivery (doses for 3% of their populations) to low- and middle-income countries in early March this year. Some of those countries, with more than enough vaccines, had already begun to extend their vaccination campaigns to their lower-risk groups whilst many developing countries are yet to complete or even start vaccinating their high risks population.

Kate Elder, senior vaccines policy advisor of the MSF Access Campaign explains that it's not just about fairness to vulnerable and neglected people in developing countries. "Even if you are just looking at it from a public health perspective, if you can prevent the disease from circulating, it's to everybody's benefit. It makes total sense of saying equity of access of COVID-19 vaccines is critical." She further explained that the emergence of recent virus variants in the midst of global transmission becomes more worrying, and as we are all part of the global community, no countries are likely to be spared. She cited the United States, the country she lives in, as an example. "If there is another variant of the virus that is replicating in some other parts of the world, eventually it's going to make its way here to the United States. So, there is no point in herd immunity in one country if you're not looking to achieve equity of immunization across the globe."

Global spirit of solidarity is needed to put a halt on COVID-19

The spirit of solidarity can be as simple as donating vaccines to developing countries that critically need them for their vulnerable groups. Some governments like the UK, Canada, France and Norway promised to share vaccines with developing countries, but it's not clear when the donation of surplus doses will begin, and urgent supply of COVID-19 vaccines are needed now. If these countries will only donate doses after they have completed inoculating their entire populations, the world could be in a much worse position as the virus continues to circulate.

"It would be indefensible if some countries started to vaccinate their lower-risk citizens while many countries in Africa are still waiting to vaccinate their very first frontline health workers,” said Christine Jamet, MSF director of operations. “This totally goes against the World Health Organization's equitable allocation framework."

There are other dangerous behaviours that could damage everyone. Blocking the export of vaccines and their raw materials and manipulating intellectual property rights to monopolise life-saving biomedical or medical technologies may prolong the pandemic and put even more lives at risk.

For example, South Africa and India sponsored a proposal regarding the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) in the World Trade Organization (WTO) last October. It proposes to allow WTO members to temporarily waive the intellectual property rights on medical tools and technologies for COVID-19 preventions and treatments if they need to. However, high-income countries have been standing in the way of the waiver proposal and the discussion went into an impasse. Only when the US government changed its position to support the waiver on COVID-19 vaccine (Note: not on other COVID-19 medical tools) in early May, some countries that opposed the proposal showed willingness to further discuss it.

This proposal may not be a silver bullet to rectify the current situation right away, but it is indeed a huge step that could help the availability of medical tools and technologies for COVID-19 in the near future. Many other developing countries and civil society organisations around the world, including MSF, hope that the TRIPS waiver will be accepted and approved by all the member states in the end.

Only when all countries can take part in research, development and production to let diversity flourish, will there be a chance for us to bid farewell to the scarcity of lifesaving medical supplies and tools, and thus the COVID-19 pandemic.