After enduring the COVID-19 pandemic, I returned to work at the MSF Hospital in Bentiu, South Sudan, three years later.

I still vividly recall my time providing health care here in early 2020, when South Sudan had yet to experience the impact of the pandemic. Fast forward to 2023, and we've navigated through isolations, lockdowns, shortages of face masks, and daily RATs. Yet in here, it seemed like COVID-19 did not leave a trace. For the people of South Sudan, who continue to grapple with conflicts, poverty and diseases, the pandemic was just like a minor hiccup. Our worries about dining in restaurants at night or testing negative on an RAT can't compare to their daily struggles.

On returning to my old workplace, I warmly greeted and hugged my local colleagues with whom I had worked closely. Three years have pass, and they've remained steadfast in their commitment to serving their community, refusing to abandon their homeland for a better life. I hold immense respect for their dedication.

After a swift handover from an American surgeon, I donned my surgical scrubs, ready to treat patients again. I feared the rustiness that might come after a three-year hiatus from the field, but thanks to my resilient colleagues, I quickly regained my rhythm!

On my first day back, the first call was from the emergency room. We admitted three patients involved in a traffic accident. The first was an elderly woman with a broken collarbone, whose situation was not serious and only required pain management. The second was another woman with extensive wounds on her knees and arms but no fractures; she needed immediate wound care and follow-up skin graft. The third and most severely injured was a boy with open fractures in both legs caused by a heavy object falling from a height. His feet were hanging in a horrifying manner.

All three patients were Sudanese. Sudan is experiencing intense conflict at the moment, and in order to flee from it, they had risked their lives journeying to South Sudan on a heavily overloaded truck, which overturned due to torrential rains, leading to severe casualties.

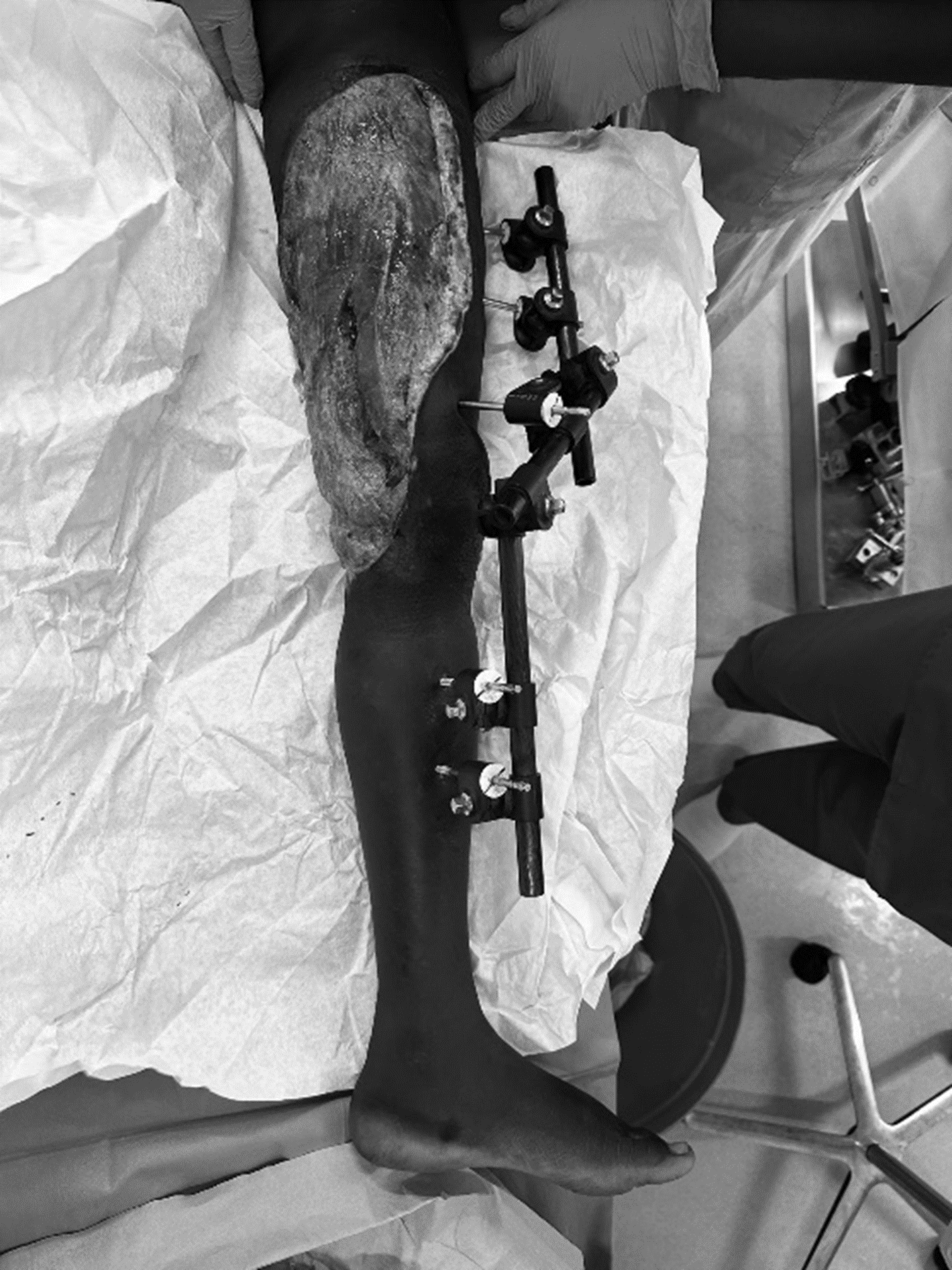

I attended to the boy's injuries, ensuring that his blood vessels and nerves were intact before proceeding with a fixation procedure. In such a devastated, underdeveloped region, most fractures are highly contaminated. Operating theatres here can hardly meet the aseptic standards of those in developed countries, so we mostly use external fixators for fractures. Despite their bulkiness, they reduce the risk of infection associated with internal fixators and are vital tools in conflict zones.

However, due to a lack of X-ray equipment, we had to rely on clinical experience and bone examination, essentially assess the degree of bone injury by touching the open wound. And don’t expect we can rely on X-ray image-guided devices to assist us in inserting metal pins at the optimal location and depth during the surgery. Put it in another way: everything was based on estimation! Yet this also demonstrated what could be achieved with limited resources.

After two hours of intensive work, I successfully fixed the boy's lower legs. We expect his leg injuries to heal in about six to eight weeks, enabling him to walk again.