Panama’s The Darién Gap: “A dangerous, inhumane route”

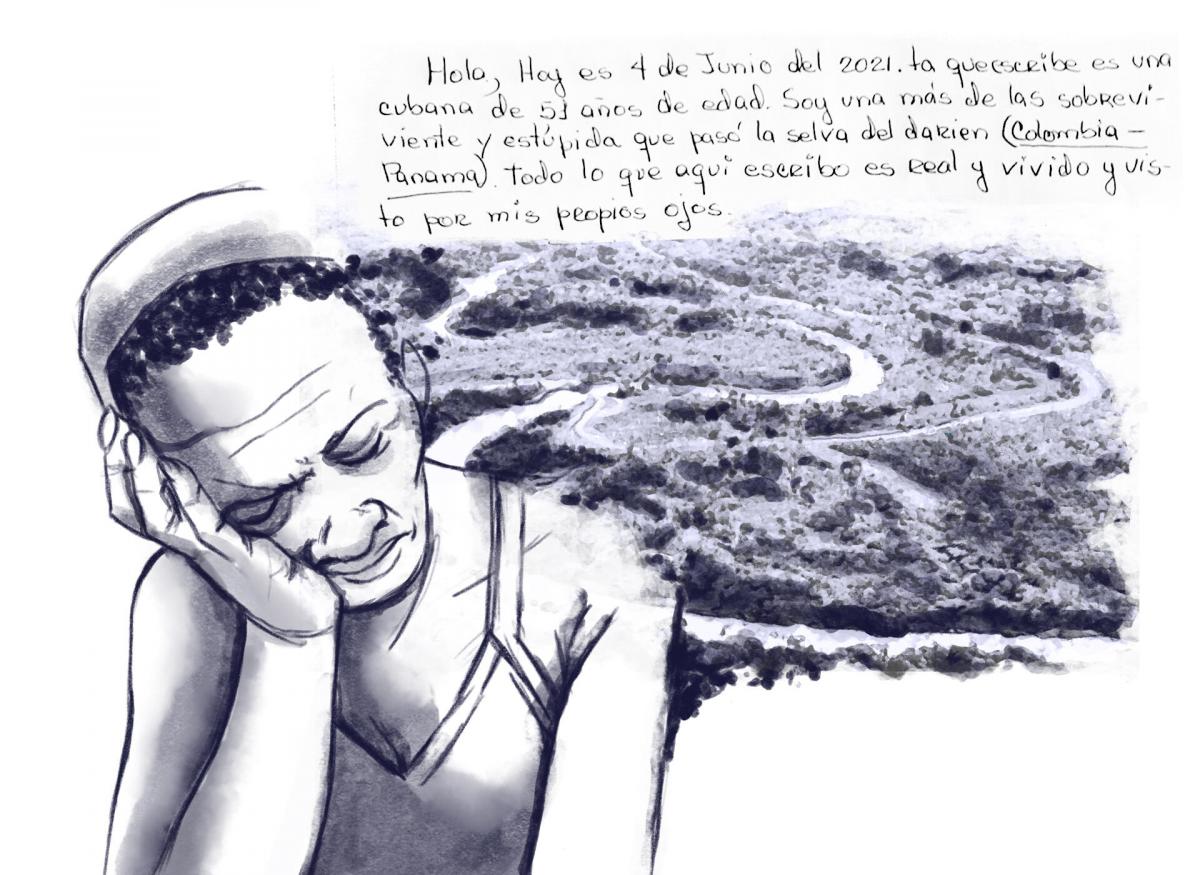

Using the story related by a 51 year old cuban woman who survived the Darien, this is a representation of what she lived inspired by. ©MSF/Jorge Montoya

In 2021, the number of people risking their lives while crossing the Darién Gap, a treacherous, roadless, 60-mile (97-kilometer) stretch of jungle connecting Colombia with Panama, has spiked. The vast majority of the more than 15,000 migrants who crossed the Darién Gap between January and May this year were Haitians and Cubans, though recently, many Venezuelans are also taking this route. Africans, Indians, and Bangladeshis who’ve entered South American countries that don’t require a visa have also crossed the Darién Gap on their way to North America. People who make it through often report seeing the dead bodies of those who did not. An unknown number of migrants do not survive this dangerous passage.

*María is a Cuban migrant who arrived in Bajo Chiquito, Panama, after her perilous journey through the Darién Gap. In Bajo Chiquito, she received medical treatment from Doctors Without Borders/ Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), and she gave the MSF team this letter to share.

Hello, today is June 4, 2021. The person who is writing this is a 51-year-old Cuban woman. I am one of the survivors who stupidly crossed the Darién jungle from Colombia to Panama.

I walked through the jungle for five nights and six days. On the first day, we climbed a high hill with a straight and wet slope called the Loma del Desafío [Hill of Challenge]. They tell you that when you cross over it, you have already done it all (a lie). After that hill comes the worst—the paths lead you to the Loma de la Muerte [Hill of Death]. Those who can do it cross over the Loma de la Muerte in one day.

It is the Loma de la Muerte because it has a horribly steep slope, and you walk along paths where there is nothing on either side. You cannot look down because you run the risk of falling and losing your life.

©MSF/Jorge Montoya

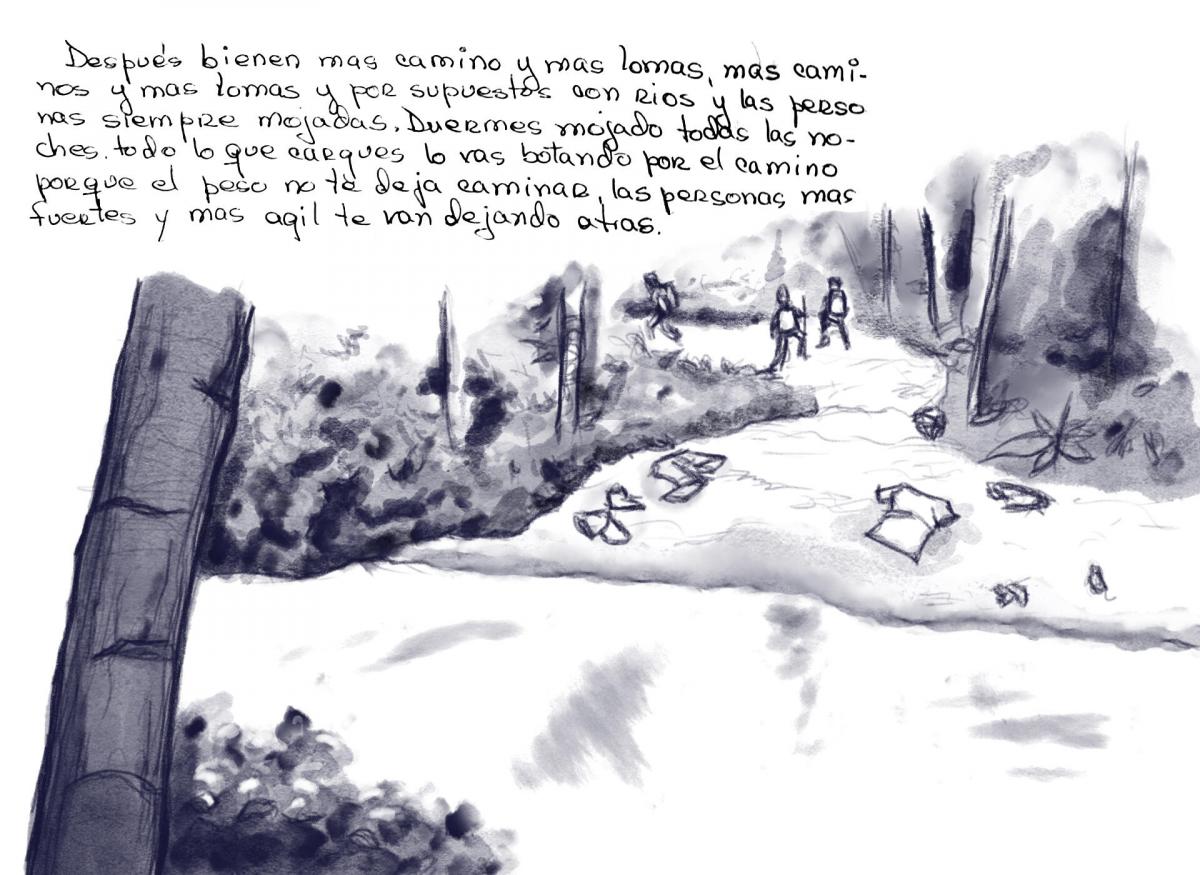

After that, there are more paths and more hills, more paths and more hills, and, of course, rivers, and you are always wet. You sleep wet every night. Everything you carry you throw away on the road because the weight holds you back when you walk.

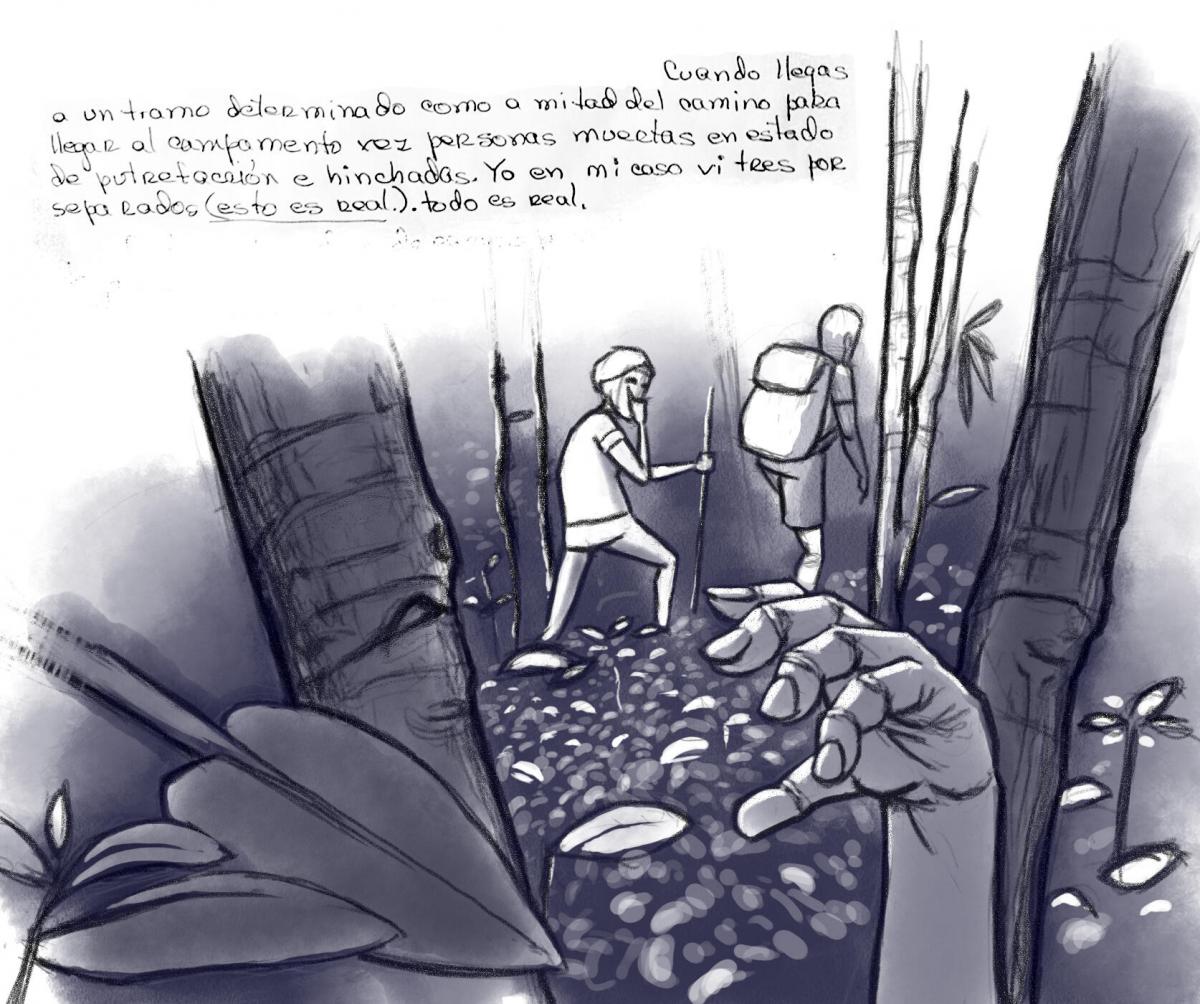

The strongest and most agile people leave you behind. When you get to a certain section about halfway to the camp (in Bajo Chiquito, Panama), you see dead bodies, swollen and decomposing. In my case, I saw three dead bodies, separately. This is real. Everything is real.

Two or three days before reaching the camp, seven or eight young people assault you; they're armed, they take your food, mobile phones, and money, and rape women with nice bodies. But the worst is not over yet.

©MSF/Jorge Montoya

You meet people who have been walking through the jungle for 27, 15, and 10 days because they have problems with their legs, and they have nothing left. You meet men and women with children of all ages.

I saved a healthy 6-month-old baby girl. She fell from her father's arms and, luckily, I was behind them on the lower part of the hill, and I was able to grab her by her right foot just when her head was about to hit a rock. The girl was saved, thank God.

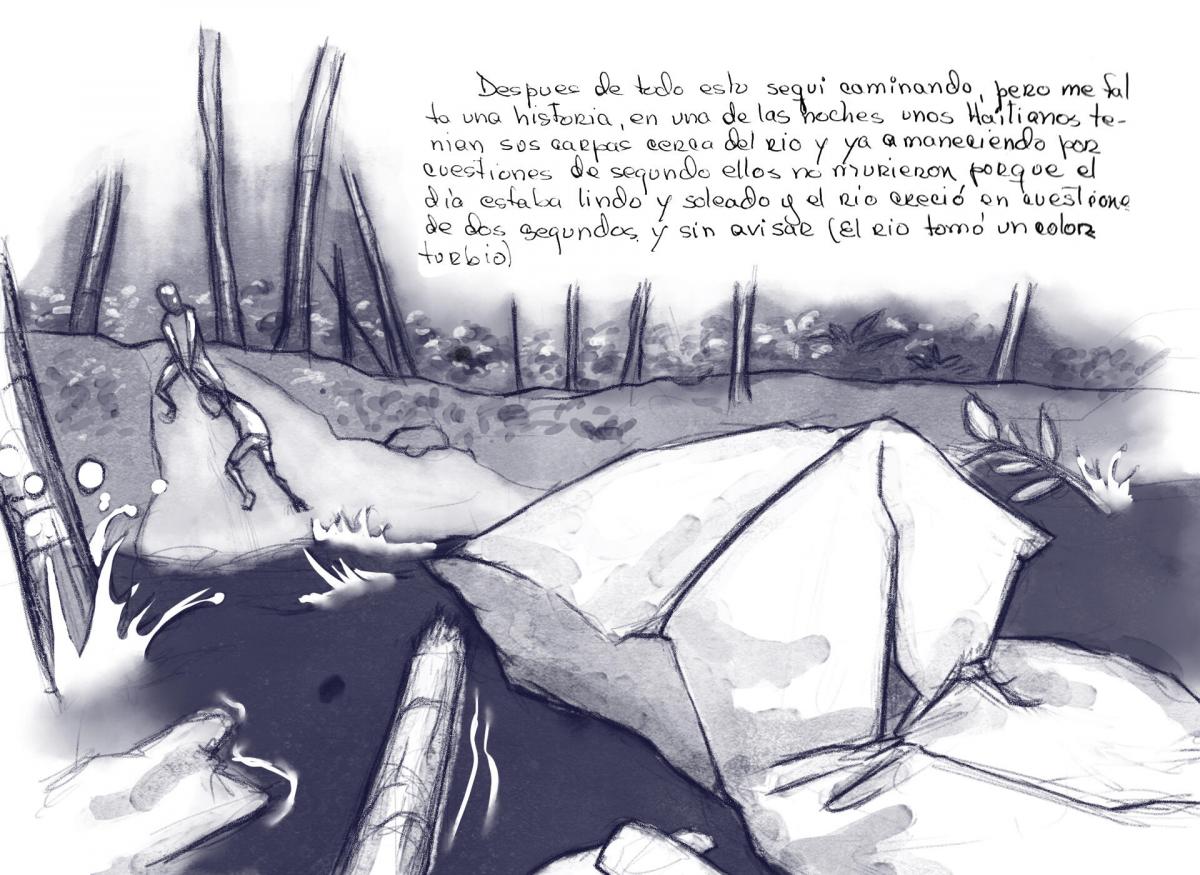

In that jungle, I ended up walking and sleeping alone. My feet hurt (they were bare, with the skin peeling and falling off). After all of that, I kept walking. But I have one story left. One night, some Haitians had set up their tents near the river. At dawn, in a matter of seconds, they nearly died because the river suddenly rose without warning, despite it being a nice, warm day.

I arrived at the camp in Bajo Chiquito on June 3 and went straight to see the people from MSF because I was unable to walk with my feet swollen and bare. I have received treatment from them twice, and they are doing an admirable job.

©MSF/Jorge Montoya

That is why I have written this, but I'm also doing it to discourage people from taking this route. The Darién Gap is a dangerous, inhumane route. It is a route on which only God saves you, but it is not a route of God. It is a route where families have to split up, even if you don't understand why. It is a fight for survival. The more days spent in the jungle, the greater the risk that you will die, you will be killed or bitten by a wild animal or a snake. They say that so many people have passed through there, it is now a road. But it is the opposite; it is a worn path with a risk of your slipping and dying. People with broken bones are left behind; those who cannot make it to the end are abandoned.

I encourage people who have traveled this route to tell the truth. There are many better ways than this to get to the United States. There is no need to despair, but you do need to make a good decision.

You will not want to remember this story. Take care of your life and love it always. Do not risk it so that God can take care of you, too.

The Darién Gap is an extremely hazardous migration route. The Colombian and Panamanian authorities are responsible for providing protection to migrants in their territories, regardless of migrants’ administrative status. States must guarantee a safe route that does not expose migrants to situations that endanger their lives or dignity.

*Name has been changed to protect the identity of the writer

Leave a Comment