Fighting Ebola

Having ravaged parts of West Africa for a year, the Ebola outbreak is on the decline. There is a substantial decrease in the number of patients admitted in the Ebola Treatment Centres (ETCs) run by MSF in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. The unprecedented outbreak has prompted the organisation to mobilize massively, deploying over 700 international staff. As of late February, MSF-HK has sent 27 field workers, including Dr. Natasha Reyes, who was in charge of coordinating MSF’s medical activities in Liberia, as well as Chiu Cheuk-pong, the first Hong Kong health worker in an ETC.

Unknown

Natasha was in Liberia in October and November 2014. Currently working as the Manager of the Emergency Response Support Unit of MSF-HK, Natasha has extensive experience managing disease outbreaks, including cholera in Sierra Leone, and measles and hepatitis E in South Sudan. Although MSF knows more than anyone else about how to handle Ebola, Natasha says there were still many gaps.

“The previous outbreaks where MSF intervened were small in scale, geographically contained and in remote locations. This is the first time we faced an open epidemic reaching urban areas, the first time we set up ETCs with over 100 beds. We did not come in completely unprepared or unknowledgeable, but the scale of the past outbreaks did not allow us to gather much information. There is the one positive thing that has come out this time: now we know much more about Ebola, and that will help tackle future outbreaks,” Natasha explains.

So far, medical care for Ebola patients is limited to supportive treatment, boosting their own immune system to fight the virus. “Even though studies have been conducted on various methods such as using the blood plasma of Ebola survivors, there is no firm evidence that they can kill the virus.” says Natasha. But MSF has been participating in clinical trials of experimental drugs, hoping to help find out as much as possible about potential treatments.

What is also uncertain is the evolution of the outbreak. In spite of the downward trend of new cases reported, contact tracing remains a serious weakness. The epidemic can be revived with one single new case. Natasha took the initiative to deploy a “hotspot response team” to the communities on the periphery of Monrovia, the capital, where other organisations were not present tackling small outbreaks. “The 15-member team had to travel for 2 days to reach a hotspot, and build a small treatment centre within the next 48 hours.”

Stress

As the medical coordinator, Natasha was also responsible for the health of over 1,000 MSF staff in Liberia. “If a colleague got infected with Ebola, it would definitely be very difficult for them and their family. However, the implications are beyond that: team morale would be affected, local communities might lose confidence in MSF, and more importantly, after years of civil war health workers are very rare in this country. Not a single doctor or nurse can be lost! We must ensure that they live beyond this epidemic so that they can save more lives in the future.”

Before the outbreak, there was only one doctor per 100,000 people in Liberia. As the epidemic has claimed the lives of many health workers, the health system is now even more fragile. Natasha points out that the outbreak has almost paralyzed the health system of the three West African countries, yet the entire world has focused its resources and efforts on addressing Ebola, seriously neglecting non-Ebola health needs.

Field workers are not invincible. Getting sick with flu or food poisoning can be very common and it matters even more in Ebola projects. “If a colleague gets flu, it is normal that he would infect 3 or 4 people and that fever from flu might seem like Ebola. Even if they know that the chance is very slim, they cannot help getting stressed, thinking that it could be Ebola.” Natasha had to order colleagues to self-quarantine and rest.

Dilemma

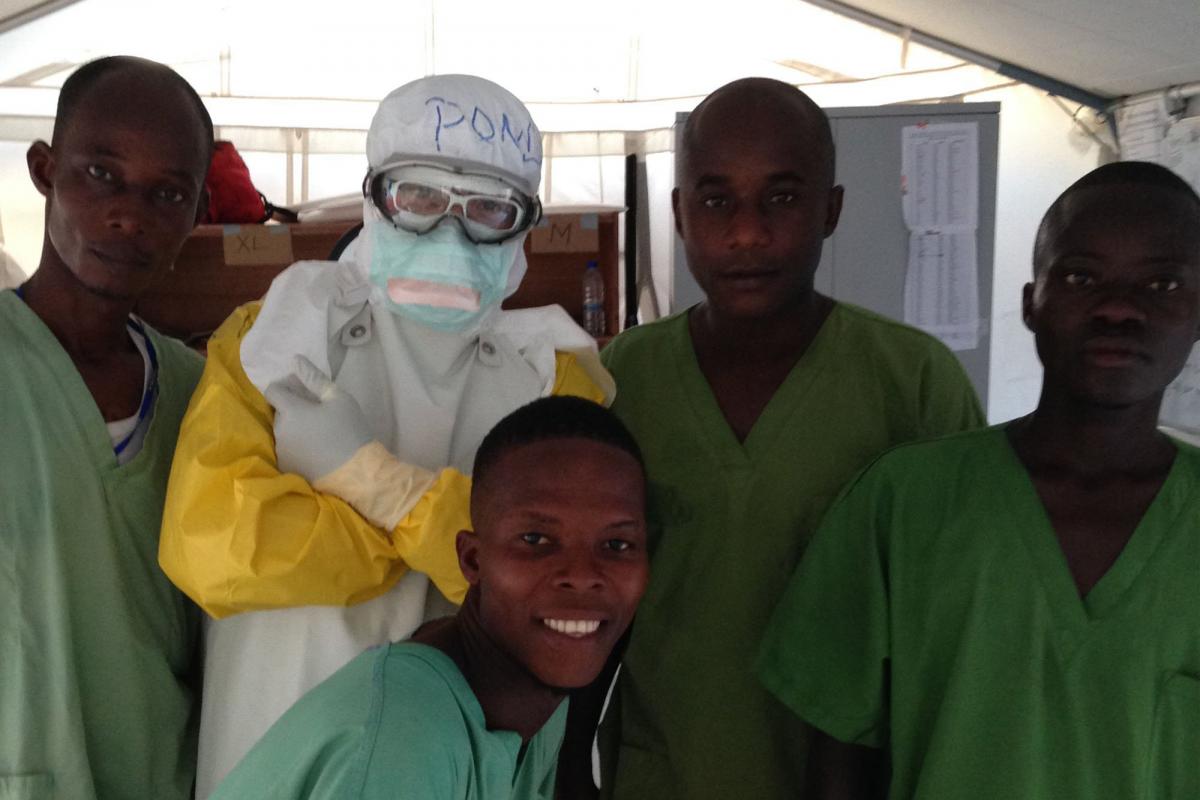

Trained as an accident and emergency nurse, Chiu Cheuk-pong (Pong) was in Liberia in November and December 2014 and worked in the front line of MSF’s biggest ETC in Monrovia – the triage. He had to determine if new arrivals should be put into the high risk zone for a further blood test. That critical decision depended on their medical condition, place of residence, occupation and contact history, especially if they had attended funerals or been near dead bodies.

“The most difficult bit of the triage is to deal with borderline cases”, says Pong. ‘For instance, Ebola and malaria have similar symptoms, and malaria is very common here; some patients might deliberately conceal information or give ambiguous answers. I cannot simply put everyone into the suspected area, because that would increase their chance of getting infected from unnecessary exposure and make them feel anxious. But I also have to ensure that I didn't let the wrong person out.’

Even tiny, seemingly inconsequential things such as trimming fingernails meant another difficult decision. “The gloves could get thin or damaged if my fingernails are too long. But I might create a wound, especially a small, invisible one when I cut my nails. And that makes an entry point for the virus. Holding the nail clipper, I pondered the probability of both scenarios. In the end, I did not get my nails trimmed throughout the mission,” Pong laughs.

Endurance

From time to time, Pong had to enter the high risk areas to assist his colleagues. He had to wear full Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), which includes scrub suits and pants, goggles, mask, head cover, plastic apron, waterproof gown and rubber boots. So health workers are well protected but it makes caring for patients more difficult.

“Health workers in hospitals in Hong Kong often give intravenous (IV) therapy, which involves inserting an IV line inside a patient's vein”, explains Pong. “This procedure is exceptionally complicated to perform in an ETC: two sets of gloves reduce sensitivity of the fingers, googles fogging up hinders visibility; and the stifling protective suit makes it hard to stay focused. It is really not easy to be accurate given all these. The entire procedure has to be carried out slowly to prevent needlestick injury. In the end, it takes at least 10 minutes to complete a procedure which can usually be done in two or three minutes.”

Liberia is as hot and humid as summer in Hong Kong. One can get drenched in sweat even without the PPE. “When I took off the gloves, I could see my sweat accumulated inside, which was enough to fill a tiny fish pond!’ Pong laughs again.

Since the Ebola outbreak was declared, MSF has provided care to nearly 5,000 patients – almost 20% of all reported cases. Currently, the organisation has over 2,000 staff working in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone.

The core

Given the constraints of the full PPE, health workers are restricted to working only twice a day in the high risk areas, with each shift lasting a maximum of one hour. Ebola survivors therefore play a crucial role in Ebola care, as so far there is no report of reinfection. They can remain inside far longer with only light protection.

Ebola survivor Salome Karwah is now working as a mental health counsellor in the treatment centre in Monrovia. Her parents, fiancé, sister and niece had all fallen sick. Salome still remembers vividly the moments she was severely ill. “I barely understood what was going on around me. All I could feel was severe pain inside my body. The feeling was overpowering. Ebola is like a sickness from a different planet. It comes with so much pain, the kind of pain that you can feel in your bones…” Gradually, Salome’s condition improved, but her parents passed away.

Salome is very sad at the loss of her patients, yet she believes that she survived Ebola for a reason. That drives her to return to the treatment centre, helping other patients to recover. “I talk to them about my own experiences. I tell them my story to inspire them, and to let them know that they too can survive.”

The rear

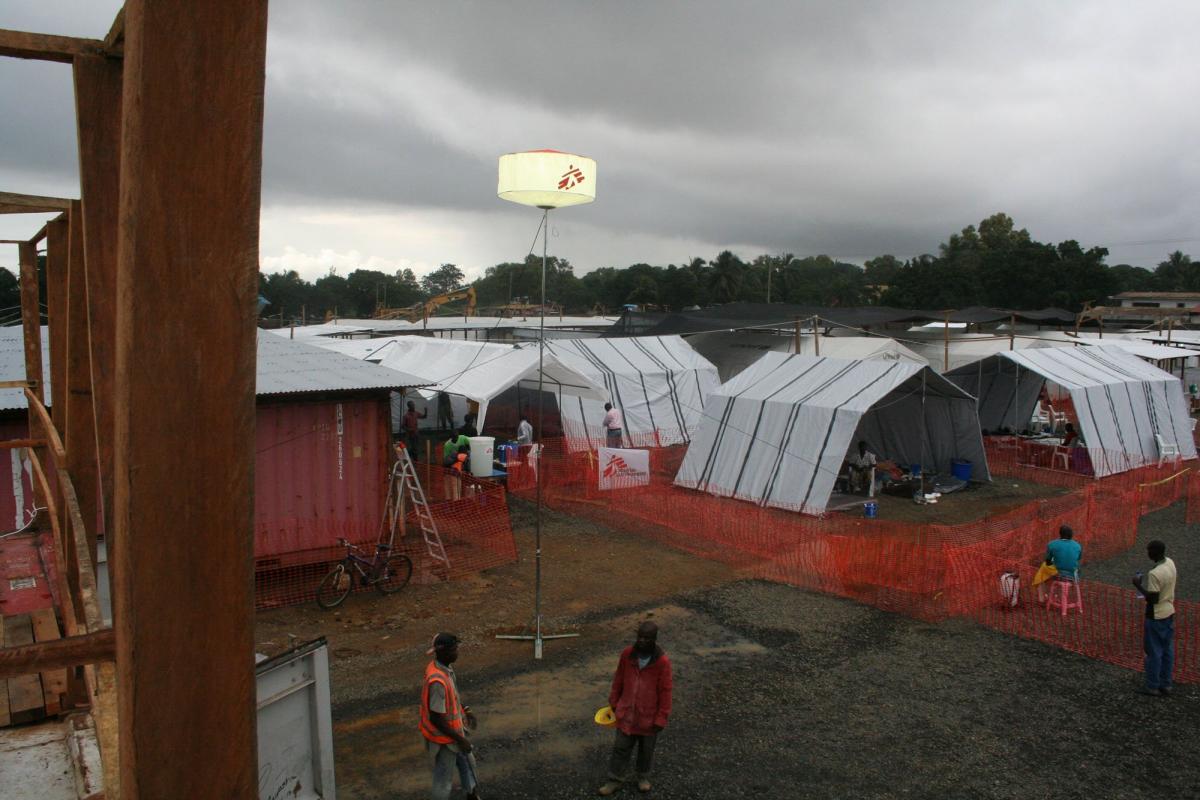

Logistical staff are equally indispensable in the fight against the epidemic. When they build an ETC they have to take into account that nothing entering the high risk zone can come out, except personnel. Scanners, for instance, are installed inside to allow the transfer of patient files electronically. Yet, if any medical equipment or other devices fail to function, technicians have to enter in full PPE for repair.

Hong Kong engineer Lucy Lau worked as a logistician in Bo, Sierra Leone. A large part of her job was to prevent the spread of the virus. ‘It is actually quite safe in Bo. But we have to regard the ETC as a high security prison, installing fences and restricting entry!’

Lucy also saw some of the wider effects of the epidemic. “The local economy is severely impacted. No one is building new houses. The temporary workers who helped us build the ETC say it is impossible for them to look for another job.”

So while the fear of Ebola has yet to subside, the societies that were invaded by it will take a long time to recover. MSF still has a lot to contribute there.